Functional Breath & Core for Low Back Pain

The most common advice given to those seeking relief from back pain is to strengthen their core. On one hand, this is good advice, since inefficient core stabilization is often at the heart of—not only back—but most chronic musculoskeletal pain. However, effective core exercise guidance is often missing. What exercises do you think of when you hear "strengthen your core?" Crunches, bicycles, and leg lifts are common answers. Yogis might also throw in the Boat and Plank pose. While these exercises target part of the core, they often miss the most crucial parts--subtle alignment details and the breath. And I don't mean ujjayi breath that is typically used in yoga. While ujjayi breathing has some powerful components, it is not the same as a functional breathing pattern.

“While ujjayi breathing has some powerful components, it is not the same as a functional breathing pattern. ”

Functional breathing patterns are at the heart of movement prescriptions for chronic pain, dysfunction, and stress. A beautiful visual example of functional core and breath can be seen in most 1.5-year-old babies as they engage playfully in the world around them. The next time you have the privilege to watch a little one toddling around in a diaper—squatting, reaching, and lifting, notice how they breathe, the organization of their spine, and the fullness of their belly. You will be witnessing the most natural and perfect core at work.

“Functional breathing patterns are at the heart of movement prescriptions for chronic pain, dysfunction, and stress.”

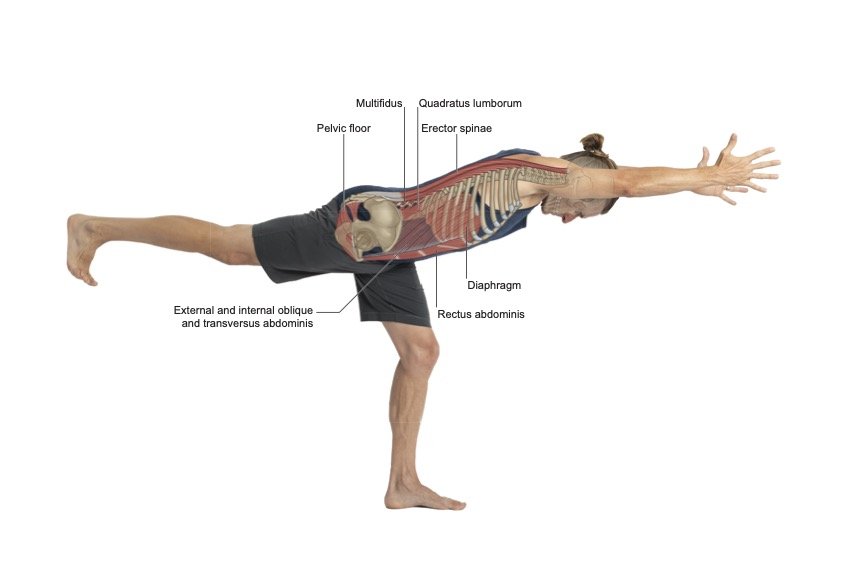

Illustration from Embodied Posture / 2022 © All Rights Reserved

Chronic stress, anxiety, trauma, injury, and habitual postural patterns dim down the natural functional core activation we had as infants. The changes appear in many ways in the musculoskeletal and nervous systems, and the switch from primary to secondary breathing muscles is part of the picture. An efficient diaphragmatic function is replaced with hyperactivity of the secondary breathing musculature, which means our upper bodies begin to work excessively, and the diaphragm becomes inhibited with every breath. Postural patterns are interesting and sometimes strange, and we adopt them for various reasons, one being aesthetics. How many of you can relate to a lifetime of sucking in your belly to look “trim,” or to get those skinny jeans on? Unfortunately, this habit hasn't served us so well for functionality and wellness. Functional breath and core invites us to embrace a full, strong belly (not the same as pushing the belly out or letting it hang out freely).

Now, pause to notice where you feel your breath in your body. Aim to keep your upper body quiet while sensing your inhalation drawing toward your pelvis. This descent of the inhale is the diaphragm dropping downward and outward in a 360 fashion. This pattern is not the same as what many call "belly breathing." It is similar, yet we want the breath to be felt in the side waist and the lower back—not just the belly. Belly breathing is ok when there is no demand on the body and you are relaxed, such as when lying down; it is an excellent way to invoke a parasympathetic nervous system response, calming somatic stress reactivity. However, when the spine (and the entire body) needs support, the breath should expand downward and outward in all directions. To do this 360 breath, two components are necessary: neutral rib-to-pelvis relationship, and abdominal wall activation. Both of these elements are explained below.

“Chronic stress, anxiety, trauma, injury, and habitual postural patterns dim down the natural functional core activation we had as infants.”

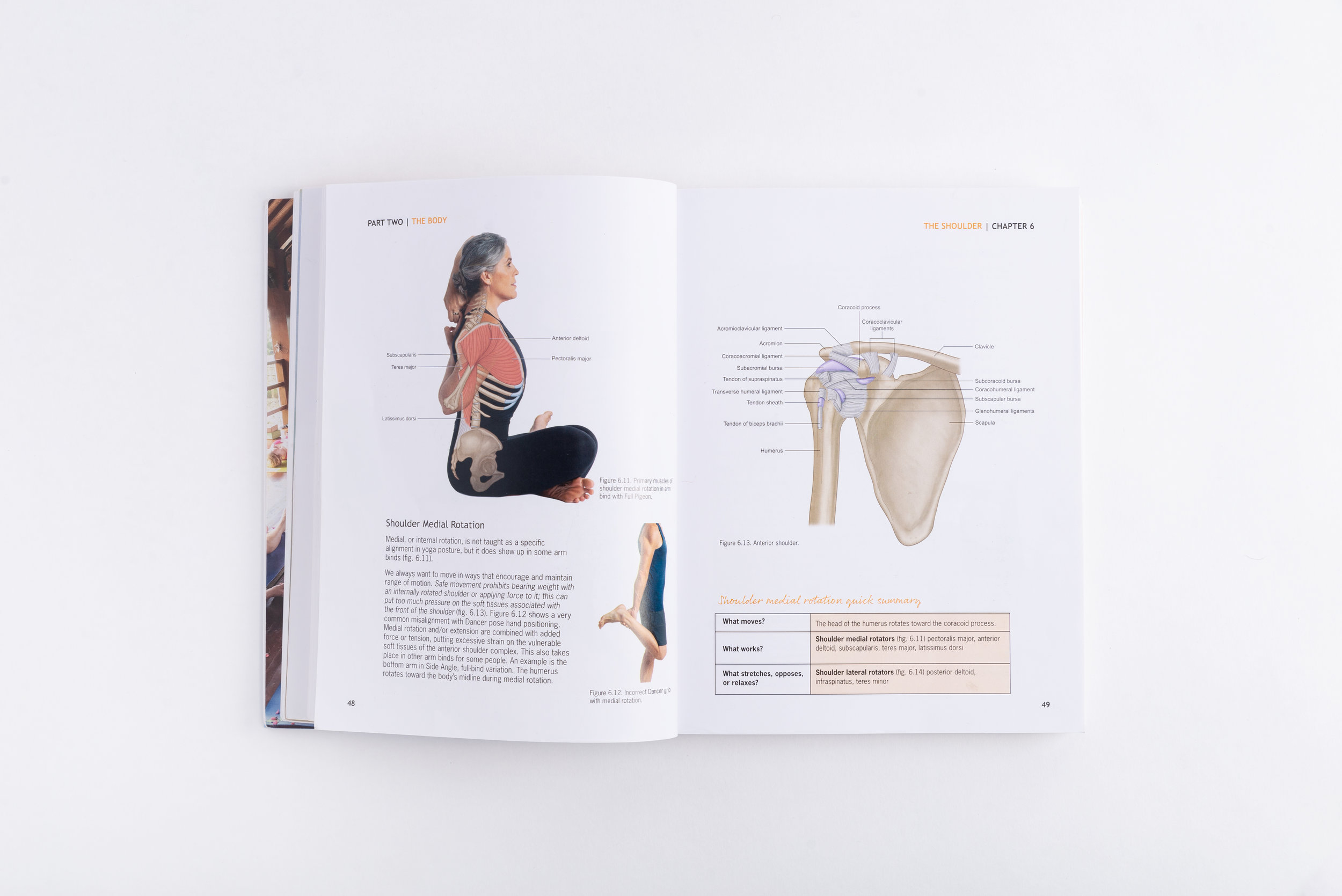

Illustration from Embodied Posture / 2022 © All Rights Reserved

The crucial thing to get here is that the 360-breath is an integral part of the functional core. Core work that does not include this and other mentioned elements will most likely exacerbate any body and nervous system imbalances. So, for example, when ujjayi breathing is taught with a hollowing out of the belly (or intense navel to spine), proper diaphragmatic descent is probably not happening, which will encourage continued secondary (sympathetic-stress) breathing mechanisms.

Another critical functional core element is the proper organization of the rib-to-pelvis relationship. This relationship is a graspable way to sense and feel spinal alignment. When the rib-to-pelvis relationship is neutral, the spine is also. An example of losing this neutrality is in the Plank pose, when ribs tend to flare toward the ground, or in a Boat pose when the back rounds. This loss of organization is also common while sitting, standing, or running. A neutral rib-to-pelvis relationship will encourage the most efficient descent of the diaphragm, as well as the most evenly spread (and injury-preventative) loads throughout the body. It helps to think of suspenders between the rib points and hip points that stay snug in just the right position to avoid backward bending or forward rounding. Think of creating the perfect container for the diaphragm to work fully. Keep in mind that while moving dynamically in multiple planes, as you might when running and catching a frisbee, you won't always be in a neutral rib-to-pelvis relationship, but this is your baseline.

“This combination is all about providing some intra-abdominal pressure that becomes excellent support for the spine and the entire body.”

In addition to the 360-descent of breath and rib-to-pelvis relationship is the proper activation of the abdominal wall. This combination is all about providing some intra-abdominal pressure that becomes excellent support for the spine and the entire body. The abdominal wall is activated to provide stabilization and resistance for the diaphragm. To activate the abdominal wall, I cue something called "love-punch readiness." Imagine how you would activate if someone came at you suddenly with a friendly little tap or punch to the belly. This stiffening is your abdominal wall, which works in concert with the diaphragm to create the functional core. Try this now, combined with a neutral rib-to-pelvis and 360 downward breathing. Can you sense the supportive intraabdominal pressure? The hope is to get this to happen again naturally, without thinking about it—just as it happened when you were an infant.

Another integral core part is the other diaphragm, the pelvic floor. This topic is an extensive one that I will cover in a separate article.

While I am not suggesting that you should always go around activating the functional core, I recommend considering its use along a spectrum or as situation-specific. So, for example, a little is necessary while sitting at a desk or driving, and a lot is needed while running, working in the yard, or lifting heavy things. The idea is to reeducate the patterns so they become automatic again. **Important to note, because the pelvic floor is part of the functional core, special guidance may be needed when there are pelvic deficiencies.

In summary, there are three primary components to functional core work:

1) Downward and outward 360-expansion with the inhalation

2) Rib-to-pelvis relationship Awareness

3) Abdominal wall activation or "love-punch readiness."

And remember, core activation is situation-specific. The best way to strengthen your functional core is to learn the subtle elements explained here and then apply them to ALL dynamic movement. Bicycles and crunches are ok, but the best work happens in the midst of real-life movement.

Stay tuned for my next article on the pelvic floor as part of the functional core!

2022 © All Rights Reserved Stacy Dockins/The Yoga Project, LLC

Stacy Dockins, MS Kinesiology: Orthopedic Rehabilitation & Exercise Psychology

Director of curriculum—Yoga Project School of Yoga

Author of Embodied Posture: Your Unique Body and Yoga